| Wind Watch is a registered educational charity, founded in 2005. |

We’re helpless to stop our unique landscape being industrialised

Credit: Mike Wade. Saturday February 04 2023, The Times. thetimes.co.uk ~~

Few people can be so rooted in the Upper Deveron Valley as Martin Sheed, a ninth-generation farmer at Aldunie. His family have lived in this remote and beautiful spot since the first Mrs Sheed and her seven sons arrived in the glen to found a dynasty in 1670.

Their bones and those of many of their descendants lie in the graveyard of Upper Cabrach church.

Sheed, 45, vows he will never leave his home, not even if it changes beyond recognition. As well it might, with wind farm developers queueing up to cash in on the Scottish government’s rush for green energy.

“There will be nothing here but turbines the way things are going,” Sheed said. “It’s already so strange to see it now, compared to how it was. The community is of the opinion that we have had enough. Most folk would say: ‘We’ve done our part’.”

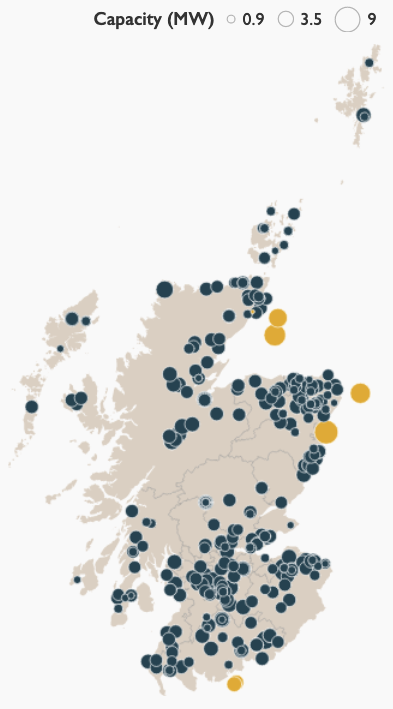

Onshore and offshore operational wind farms in Scotland. The size of each circle is proportion to the capacity of the farm in megawatts. Map data: © Crown copyright and database right 2019. Map: The Times and The Sunday Times. Source: Department for Business, Energy & Industrial Strategy.

An open letter this week, signed by businesses, community associations, individuals and politicians made the point. It called for a halt to wind farm development in the valley pending an inquiry into the impact of the turbines.

Two developments, Clashindarroch, with 18 rotors, and Dorenell, south of Dufftown, with another 59, are already established in the valley. They are a visual intrusion and a source of noise pollution and flickering light, say residents.

But though the Cabrach is already deemed to have reached “saturation point” according to two independent reports, turbine numbers are set to soar with 68 more proposed. The new structures are set to be 200m tall, more than twice the height of Glasgow University tower.

Four more wind farms are at the planning stage. Another, at Garbet Hill by Auchindoun, was thrown out by Moray council, only to be called in by the Scottish government reporter and approved.

In the Cabrach, you can hear the existing turbines “like a helicopter that never arrives,” as Sheed put it. Anger generated by the “industrialisation” of this beautiful landscape is a good deal louder.

Much of the rage is directed at planning officers in offices in the central belt, who, protesters say, couldn’t find their way to the Deveron Valley and will not have to live with the consequences of their decisions.

Derek Ross, an independent Moray councillor for Speyside Glenlivet, is livid. “We made a decision on Garbet Hill and it was reversed. It’s just an insult to democracy,” he said. “Our decision was overturned by someone in Edinburgh. If devolution has to mean anything, it means devolving to communities. That is not happening in Scotland. It’s a real democratic deficit.”

The same complaint is everywhere. “We don’t feel we’re being listened to,” said Patti Nelson, chairwoman of the Cabrach community association. “We are in a fragile community and it’s being damaged. They are changing the area in ways that will destroy all the unique things about it.”

Euan Cameron, an engineer, can trace his roots in the valley back five generations. Like everyone that The Times spoke to, he is a strong advocate of the transition from fossil fuels.

The trouble is, he said, “the Scottish government is pushing for development at any cost. The key question I’d ask is what is the value of a community? What will happen when the area is industrialised? It is practically irreversible. There is a balance to be struck.”

A huge source of anxiety is the SNP-Green administration’s energy strategy, published last month. In theory, Scotland already has enough turbines to generate 8.4GW of power, well over half the UK’s total, but Nicola Sturgeon’s government wants to add a further 12GW.

The visual effect of the target is mind-boggling and not just for people living by the River Deveron. From Skye to Sutherland, in Dumfriesshire and the Scottish Borders, locals are raising fears about the sharp growth in the number of turbines.

People question the phrase “just transition”, when turbines have such a severe effect on rural communities, many of which are already overlooked by wind farms. Marc Day, a professor of strategy and business management who lives at Haugh of Glass, has been looking at the figures.

“If you think you have already got lots of wind farms in Scotland, you ain’t seen nothing yet,” he said. Day raises questions about community benefit funds, paid by wind farm developers, which he believes are too low to be fair to residents.

“Will people want to live among 150 wind turbines? Even if they are resigned to that – what is the community benefit?” said Day, who teaches at the Henley Business School, part of the University of Reading.

“The community benefit figure was set in 2014 at £5,000 per MWh. If it had been index-linked it would have risen to £6,500 per MWh. That makes a massive difference to the big pot of cash we ended up with for my community.”

Ironically, the politician who set the figure was Richard Lochhead, MSP for Moray and now the just transition minister.

Richard Hammock, a retired telecoms manager, frames a perceived injustice in another way. He insists the community is not against wind power in principle – and even acquired a turbine of its own when he was chairman of the development trust – but there is a difference in revenue.

“All the profit from our turbine goes into the community, unlike the big operators, who are based abroad,” he said. “There is little employment once the turbines are up. They’re manufactured overseas and usually erected by teams from Poland or Portugal. We tend to get less than 1 per cent of turnover.”

For many residents there is frustration that the march of the turbines comes at a moment when communities along the Deveron have revived for the first time in decades.

Jonathan Christie is chief executive of the Cabrach Trust, which aims to preserve the cultural heritage of the area and safeguard the community.

In the post-pandemic world he senses more people are waking up to the attractions of the area, just at a moment when the trust itself is expanding its influence by opening a distillery, which is expected to create 14 jobs.

“This project speaks to permanent employment, and it involves renewable energy heat recovery,” he said. “We share the Scottish government’s objectives but a big part of our regeneration vision is to attract visitors in their thousands. We know, from feedback, that a major draw of this area is the fact it’s off the beaten track. Its landscape and the natural world are huge drivers.”

The trust is a formidable body. Christie, 40, spent ten years with the Wood Foundation, the charity founded by Ian Wood, the philanthropist. Grant Gordon, the Cabrach Trust’s energetic chairman, is from the distilling family and wants to see long-term population decline reversed. Over the past century it is estimated that a population of about 1,000 has fallen to 100.

The trust is “trying to understand what all these new turbines might do to the community and the natural assets of the Cabrach”, Christie said. They were shocked to find they were the only ones involved in the planning battles to ask the blindingly obvious questions.

“There is a planning process around each individual development, but no one is looking at this in net terms and considering what this might look like,” Christie says. “Access roads, deep foundations, turbines – who has done the mapping or assessed the ecological impact? Is anyone actually looking at these as an aggregate issue? These are interconnected issues.”

Frustrating to the point of fury, taking on planners and wind farm companies presents another difficulty. It is hugely expensive, as Christie points out. A challenge to the energy consent planning process requires pre-submissions, full submission, attendance at hearings and meetings.

“The human resources associated with that is astronomical. We heard from Moray council directly that they [have highlighted] that the resources needed to participate is putting a huge strain on their budgets.”

“We are a small trust with finite resources. We feel we should have an important voice in decisions which are going to affect this community for generations. At times that way in which you can elevate those concerns feels very absent indeed.”

Richard Lochhead was asked for comment on the fate of the Cabrach. The Scottish government said: “Bold action is required to tackle the climate emergency. We are fully committed to ensuring that our energy transition will be fair and just for everyone – for our workforce, for the energy sector, and for the communities they support.

“We want to maximise the community benefits from energy projects, and provide regional and local opportunities to participate in our net zero energy future.”

The new National Planning Framework 4 “will make sure the planning system enables the growth of the renewable sector while continuing to protect our most valued natural assets and cultural heritage,” the government added. “Developments will be subject to impact assessments, appropriate mitigation, management measures and monitoring.”

In her home in the Cabrach, Patti Nelson has already conducted her own impact assessment. “If it all goes ahead, some of the turbines will be on top of the hill I can see from my kitchen ,” she said. “So will I be able to sit and watch the birds? Who knows? I just know that it will fundamentally alter the unique characteristics of this fantastic place.”

Technology invented by a Scot has been trouble from the off

James Blyth, a professor at Anderson’s College, Glasgow, is believed to have created the first wind turbine to generate electricity in 1887. His device was installed at his holiday cottage at Marykirk, Kincardineshire.

The electricity that Blyth produced was used to charge accumulators – storage devices that could supply lighting to a home.

The academic is said to have offered to give excess power from his system to light the village’s main street but his neighbours turned him down as they thought electricity was the work of the devil.

Today’s modern wind farms are much more advanced than Blyth’s but local distrust of such development remains.

The first modern wind farm in the UK was built in Cornwall in 1991 and the debate over their effect on the view, for better or worse, has raged ever since. The first Scottish onshore wind farm was built on Hagshaw Hill, South Lanarkshire. It went into operation in 1995 and was extended in 2006.

Few would argue about the need for more renewable energy as part of the move towards net-zero emissions but one frustration is the intermittent nature of the power being produced.

When the wind blows, lots of electricity can be produced. On calm days when the turbine blades will not turn, nothing goes into the grid.

Batteries or other methods of storage may one day help to smooth out the problem but widespread deployment of such technology has still to take place.

The growth in the overall generating capacity of wind farms is showing little sign of slowing down, however.

By 2009 2GW of capacity was installed across Scotland; by 2015 it had reached 5.3GW and by the middle of 2022 it was 8.7GW. That resulted in more than 17,000GWh of electricity coming from onshore wind in 2021.

That output is only going to grow and the Scottish government affirmed in December that it hoped to have a minimum of 20GW of onshore generating capacity installed by 2030.

Holyrood minsters estimate that there are already more than 200 projects in the pipeline which if all are completed would add 11.3GW.

Improvements in manufacturing, greater turbine efficiency and advancements in digital technology have helped to reduce project and operational costs. This means more wind farms can be built without the need for a Westminster-supported power subsidy.

Corporate buyers, including Tesco and Amazon, have already signed up to long-term power deals with Scottish wind farms as they look to decarbonise their operations.

Alongside that, Scotland still has many potential onshore sites where analysis shows that the wind will blow often enough to give a strong commercial return.

Communities, particularly in the rural and remote areas where the projects tend to be, can benefit from additional funding from the projects as well as the operations and maintenance jobs created.

Opposition to wind farms tends to come from people who object to the landscape being changed, biodiversity harmed or the nation’s natural assets damaged.

Campaigners point to data produced by Forestry and Land Scotland which suggests that 13.9 million trees had been felled between 2000 and 2020 to make way for wind farms.

What that data does not reflect is the detailed commitments each project has to make, which include improving animal habitat, reforestation, peatland restoration and the protection of flora and fauna.

While developers would like to see a faster planning process there is no doubt that current procedures provide a forum for residents and environmental groups to ask rigorous questions.

With the new generation of turbines standing as tall as 200 metres – the height of 44 double-decker buses – their impact on the landscape is unlikely to decrease.

Michael Matheson, the Scottish government secretary for net zero and energy, acknowledged critics’ concerns in December’s onshore wind strategy update.

He said the growth in capacity was essential if Scotland was to reach its net zero targets. He added, however, that this had to be delivered in a way that “is fully aligned with, and continues to enhance, our rich natural heritage and native flora and fauna”.

£28bn on the cards from wind

Scotland can generate £28 billion from the offshore wind supply chain if it “plays its cards right”, the first minister has predicted (Greig Cameron writes).

Nicola Sturgeon said the Scotwind leasing round for offshore wind could have a significant economic impact.

The successful bids for that process were identified last year and could lead to more than 27 gigawatts of new generation being developed across 20 sites in the coming years.

While some projects, particularly those with floating foundations for the turbines, might not begin operating until the 2030s others are likely to start sooner.

Scottish ministers asked for bidders to outline their spending commitments for Scotland before the winning entries were picked.

Industry estimates suggest that more than £1 billion of supply chain investment will come to Scotland for each gigawatt that is developed.

Sturgeon, speaking at the Business in the Parliament conference in Holyrood, suggested Scotwind alone was a massive opportunity for the nation.

She said: “If we play our cards right, and that is a big caveat because we have to take the decisions that make sure we realise this potential, but if we do that this has the potential to not just deliver green renewable energy for the future but £28 billion of supply chain work in the years ahead.

“So that incredible offshore wind potential we have, as that comes to fruition, it will enable economic activity and the creation of jobs.”

Sturgeon also suggested the growing offshore wind capacity could lead to the creation of a green hydrogen sector.

Using electricity generated from the offshore wind farms to power onshore hydrogen electrolysers can give a net zero version of the gas.

The Scottish government has already been in talks with German industrial customers about the growing demand for green hydrogen.

Sturgeon described that as “perhaps the biggest industrial opportunity we have had since the discovery of North Sea oil and gas”.

She added: “We know decarbonisation can create many jobs in other sectors as well.

“It is often seen as a big challenge and burden and difficult but the opportunities are potentially limitless.”

This article is the work of the source indicated. Any opinions expressed in it are not necessarily those of National Wind Watch.

The copyright of this article resides with the author or publisher indicated. As part of its noncommercial educational effort to present the environmental, social, scientific, and economic issues of large-scale wind power development to a global audience seeking such information, National Wind Watch endeavors to observe “fair use” as provided for in section 107 of U.S. Copyright Law and similar “fair dealing” provisions of the copyright laws of other nations. Send requests to excerpt, general inquiries, and comments via e-mail.

| Wind Watch relies entirely on User Contributions |

(via Stripe) |

(via Paypal) |

Share: